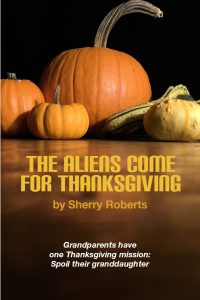

“The grandparents are coming.”

“The grandparents are coming.”

I didn’t know how to say it without making it sound like an invasion. It was Thanksgiving, and my mother and father were traveling to a foreign planet. They were Missouri pilgrims in an ancient Oldsmobile, crossing the wild Mississippi; weathering the harsh stretches between Howard Johnsons; taking on the interminable turnpike of New York. Probably an hour ago they entered Vermont, a cold distant wilderness as they called it, never letting me forget the warmth of home.

Seeing the cornered look on my face, John put his arms around me. “It’s too late to move,” he said. “Here is where we’ll make our stand. We’ve done everything we could. Raised her the best we can. We’ve given her a good set of values. I think she’ll be okay.”

“She’s only one,” I cried.

John was the dearest man to have around when relatives chose to call. He did little things to make their stay pleasant and soothing. He bought their favorite foods—black licorice for Poppy Boo, real butter for Grammalama. He took them to see their beloved action movies—with horrible car chases—and to tour manufacturing plants where little gizmos were made that Poppy Boo found fascinating.

John was also a hopeless optimist.

“Are you ready?” I asked.

“Of course. I could tell you the price of petroleum in Timbucktu.”

I curled closer to John.

Outside a car drove up, the horn blowing. Someone shouted, “Where’s that granddaughter of mine?”

***

Every morning Grammalama got up before the rest of us and loaded the table with breakfast. While John and Poppy Boo discussed economics, our daughter sat in her high chair. Lined up on Cynda’s tray were three cookies.

As Grammalama added a fourth, I said, “No more cookies, Mom.”

“Oh, a cookie won’t hurt her. You like Grammalama’s cookies, don’t you, sweetheart?” Grammalama had baked that morning too.

Across the table, Poppy Boo asked John, “What are you paying for gas up here?”

“Three twenty-five.”

My father, an expert in one upmanship, said, “We didn’t pay more than three the whole trip.”

Grammalama made goofy faces at Cynda. “Can you say cookie?”

Cynda knew three words: no, Dada, and bean, short for bean sprouts.

“We have to go shopping after breakfast,” Grammalama informed Cynda. “I can’t make anything with wheat germ.”

Although the grandparents arrived with a trunk crammed with stuffed bears, dolls, building blocks, and spinning tops, every time they went on an errand they came back with more. Poppy Boo insisted Cynda needed a train set. Grammalama thought an Easy-Bake Oven was necessary.

“She’s only one,” I reminded them as Cynda banged the caboose on the oven.

The three of them—Poppy Boo, Grammalama, and Cynda—stayed up most nights watching Jimmy Fallon. Before dawn I heard Poppy Boo changing Cynda’s diaper and sneaking her into their bed. I listened to the trio giggling and gritted my teeth. We had a rule about bedtimes and babies in bed with adults. John rolled over and slipped his arm around my waist, “Relax, we’ll get her on schedule after they leave. It’s Thanksgiving.”

And they’re grandparents, he didn’t say.

It wasn’t as if Poppy Boo and Grammalama didn’t know better. I’d told them again and again, in letters and telephone conversations the past year, how my daughter’s body was a temple, how chocolate and caffeine had never passed her lips. I proudly told them that she chose fruit over French fries.

Afraid I would fashion a turkey out of tofu, Grammalama insisted on cooking Thanksgiving dinner. I offered to make the salad while Cynda and Poppy Boo watched football games and drank Coca-Cola.

“Eileen—you remember Eileen, don’t you?—she said I was so lucky to be spending Thanksgiving in New England, where it all started,” Grammalama chattered, stirring the huge pan of stuffing with a utensil that resembled a small oar. “Eileen always was crazy about the Pilgrims. Of course, I told her all that history and ambiance is nice, but I was really going for my granddaughter. There is nothing like being with family on Thanksgiving.”

Grammalama cast a sad look in my direction. “I told Eileen, ‘Since my daughter can’t come to me, I’m going to her.’”

“Maybe next year we’ll be able to afford the plane tickets,” I said.

She started shoveling the stuffing inside the bird’s cavity, which appeared as dark as a small cave. “After all, I said to Eileen, she’s my only grandchild and I don’t get to see her nearly enough, don’t get to spoil her. A grandmother’s got to spoil. It’s my God-given right. I’ve earned it.”

I kept quiet.

“What I used to put up with when you were growing up, you can’t imagine,” she continued. “You could do no wrong in your grandmother’s eyes. When you spilled red Kool-Aid on her special white rug, she claimed, ‘We needed a new rug anyway.’ And when you broke one of her good china plates, she said she never liked that design from the day she bought it. I used to get so furious with that woman. It’s a wonder you turned out as well as you did.”

***

It was the best turkey I’d ever eaten. Poppy Boo said grace, and Grammalama sang to Cynda. John and Poppy Boo did another dissection of petroleum prices. Poppy Boo has long thought shooting was too good for OPEC. I cut Cynda a slice of pumpkin pie, which Grammalama replaced with chocolate pie. Grammalama had made both.

Two days later, when it was time for Poppy Boo and Grammalama to leave, we stood beside the car looking at each other, at a loss for words. We hugged and whispered with soft, wet eyes, “Happy Thanksgiving.”

Life didn’t get back to normal for several weeks, and more than once I found myself angry with Grammalama and Poppy Boo. John told me not to worry as we watched Cynda ensconced before the television, cackling at Fallon and demanding more Coca-Cola and cookies.

But I knew the war had just begun.

_________________________ If you enjoyed this story, please take a moment more and check out some of Sherry’s other fiction:- Down Dog Diary, Warrior’s Revenge, and Crow Calling: unusual Minnesota mysteries

- Book of Mercy: a story of a dyslexic woman who fights a town banning books

- Maud’s House: what happens when creativity goes missing in a small Vermont town

In the Thanksgiving mood? Read my essay on The Real Reason We Give Thanks.