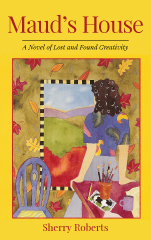

Once this house was covered with tattoos.

Pictures of trees and monsters and animals trickled from my fingers like blood. They spread over the walls and the furniture and the dishes. Scenes slithered across the undulated siding. Portraits yawned on downspouts, like the mirror faces in a carnival fun house.

Before I was born, this place was nothing but an old Vermont farmhouse. Misshapen by generations of New Englanders, every one a frustrated architect. Rooms were added as families grew, as wives squirreled away money, as whim took the owners. There was no grand plan, just a grand passion for leaving a mark.

Before I was born, this place was nothing but an old Vermont farmhouse. Misshapen by generations of New Englanders, every one a frustrated architect. Rooms were added as families grew, as wives squirreled away money, as whim took the owners. There was no grand plan, just a grand passion for leaving a mark.

I grew up here. I have those people inside of me. I too have always needed to change my world. I could never be satisfied with just sitting on a porch step and leaving life alone. There was so much inside of me, so many lively, creative itches that demanded with the volume of a fog horn to be scratched. Once all I could feel was creation. It was my food, my water, my air.

I painted here. I made my mark on everything. My house wasn’t just a house; it was a canvas, a roadside attraction. Once people went out of their way to see my house. They asked for directions in town. They asked Wynn Winchester the beautician or Frank Snowden at Snowden’s Store or the Reverend Samuel Swan as he raked the leaves in front of the church. Wynn, Frank, and the Reverend didn’t mind.

“Head north on Highway 100,” they said. “Two miles out of town hang a right on Beaver Creek Road. Probably won’t be a sign; damn kids keep stealing it. Just look for the pole. It’s a dirt road. Follow it, oh, three miles, and you’ll come to Maud’s house. Can’t miss it. You’d have to be blind to miss it. The colors scream at you, like a rock ’n roll band.”

A van full of hippies, high on Canadian weed and an Expos win, found it; “Cool man,” they said, “psychedelic siding.” So many people discovered my house, in fact, that Papa started a guest book, like the museums have, for people to sign. A record of who’d been here and what was on their minds at the time:

“Professors Skillington, Dillington, and Jones. Harvard. Interesting blend of the primitive, mystic, and totemic . . .” They spent three days with us, roaming the house, eating our food, taking notes, and shaking their heads. They found correlations between my painting and the works of the masters. I agreed with everything they said and would have gotten away with it too if I hadn’t asked, during a long monologue by Professor Skillington on the place of the horse in abstract art: “Miró, who?”

“Bill and Sally. Perryville, Missouri. The cutest little house we ever saw.” They discovered the house by accident. “Oh, look at that house,” Sally said, poking Bill in the ribs until he stopped. They came upon the house suddenly and it startled them. They stared at it as if it were a deer caught in their headlights. They got out of the car, approached it with caution, then began snapping pictures.

“Sandra, Nick, and Jack. Berkeley. Thank you.” I liked them. They arrived looking for something. They touched the house with gentleness, the way you caress the soft spot on a baby’s head. They asked if they could camp in the yard for the night. “You can camp here forever,” I said, totally enchanted by their free smiles and quiet acceptance. But they didn’t. In the morning they headed down the road, their van with the peace sign painted on the side backfiring as they disappeared over the horizon.

It was a house that called to strangers and strange people. Like my husband George. But let’s not talk about him now. George killed the house, before he died himself. George was such a stinker. He still is.

—————

On my fourth birthday, my father gave me the house, home to the Calhouns for generations, the place where my father and grandfather were born. “Gave her every nail, board, and shingle,” my father used to tell our tourists. Papa became rather possessive about the people who used to stop and admire my house; he felt a responsibility to “our tourists” and their sightseeing pleasures. He never minded when they interrupted him milking a cow or repairing an ax handle. He had public relations in his blood. “Twelve rooms,” he told them. “And Maud’s painted every square inch.”

While other parents made threats, swatted bottoms, took away television privileges, my father said: Go ahead. Go ahead and draw on the walls.

He had nothing against discipline.

He was not into pop psychology and the benefits of letting children express themselves.

My husband George said he was crazy.

I said, “No, he just loved me.”

Psychologists say concert pianists, Olympic swimmers, great mathematicians, renowned surgeons, gifted sculptors don’t succeed just because of their natural genius. They become what they become because they had mothers and fathers who provided pianos to bang, pools to swim in, toys to tinker with, frogs to dissect, clay to shape. I said, “Think of the house, George, as a frog.”

George thought of it as real estate.

—————

I knew I couldn’t keep George out of this, so I might as well talk about him. I met George the day I buried my father. There I was fresh from the funeral, wondering why everything seemed changed, banging my shins on the coffee table, when George knocked on the door. He was like all of our tourists, curious about the house. I burst into tears. That was my father’s province. Public relations. The tourists.

“I don’t understand,” I sniffled. “All my life that coffee table has been in the same place.” I rubbed my leg and looked at George in confusion. “You asked what? The house?”

George stepped inside the door, asked where the kitchen was, and took charge of my life, “You need two aspirin and an ice bag for that leg.” George’s timing was perfect. I know now George and my father wouldn’t have lasted a day in the same house. Papa didn’t like Professors Skillington, Dillington, and Jones either. He sang and danced when they left. And now George is gone, too, cracking up his car on a curve on Highway 100. Up in heaven, I bet Papa’s feeding the jukebox.

—————

Papa had been right about Professors Skillington, Dillington, and Jones; what they knew about true creation would fit on a postage stamp. Of course, I knew who Miró was. I’d read about him in a book about artists from the Round Corners Library. That’s where I got my ideas at first—from books. When I painted the pictures in the dark, narrow back stairs, I had to use a flashlight. I pretended I was a prehistoric woman in some cave in France, one of the first artists of all time, and the flashlight was flame.

A corner of the Sistine Chapel was my model for the bathroom ceiling. My father looked up as he shaved in the morning and saw men welcomed into heaven or sentenced to hell. What a way to start the day, he growled.

We ate on plates, the undersides dripping with the images of melted watches. We slept under the sensual influence of Picasso bulls. Being a farmer, I thought my father would appreciate that touch of the bucolic. Night after night, he contemplated the furiously erotic creatures strutting about his ceiling, pumped up with power and hormones and nature. He said he thanked the Lord they couldn’t get to his cows. The whole house was a canvas. The pots and pans, the tables and chairs, the grocery bags, the flowerpots, the kitchen cabinets, the rocks in the yard, the buckets in the barn. Nothing was safe.

My father constantly complained/boasted to Milky Way, our pet cow. “Oughta see what she’s done to the bathroom. I’ve had nightmares that looked better than that. Scared the shit out of me.”

“Papa!”

He’d go on, pretending he didn’t hear me, devoting his full attention to scratching the place behind Milky Way’s ear. “Told her she oughta tone down the places where a man first sits in the morning.”

—————

I have always preferred a clear and simple style. I’ve never been one for flinging paint on a wall with a big bowie knife or scraping it around with an old automobile license plate. I like a cow to look like a cow.

Back then, when I used up paint faster than Snowden’s Store could stock it, or so it seemed, I worked mostly on the large side. I painted murals so big and true they were mistaken for real life. Once, while my father was visiting Aunt Marian in Buffalo, I painted a replica of the barn door on the side of the barn. In the painting, you could see Milky Way waiting for breakfast. The first day home from Aunt Marian’s Papa trudged out into the misty morning to do chores. “Hold your horses, Milky Way,” he mumbled, rubbing his eyes, buttoning his jacket, plowing straight into the painting. Almost broke his nose.

Yes, once I was that good.

Good enough to put people’s noses out of joint.

__________________________________________

Want to read more? Get your copy of Maud’s House today. If you can’t find my books in your local bookstore, ask for them. Ask your local library to carry my books in their collections. Thank you for being a reader and supporting not only my work but those of many authors.