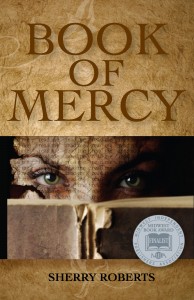

This is an excerpt from Book of Mercy, a novel by Sherry Roberts. It is a Midwest Book Awards Finalist.

THE APRIL MEETING OF THE MERCY STUDY CLUB convened in Irene Crump’s solarium, a room ablaze with rich sunlight, understated elegance, and female resolve. Here seventeen women—dressed in silk designer suits and heels—changed lives. This room, with its ceiling fans stirring air while manicured hands stirred gold spoons in demitasse cups, was command central.

The Study Club was a book club, a support group, and a force to be reckoned with. While their husbands struck deals over lunch in clubs still dominated by white males, their wives held on fiercely to their own pockets of power. When the need arose, these hothouse blooms could shake loose an amazing amount of cash and clout. They got what they wanted without breaking a sweat, raising a voice, chipping a fingernail, or bothering with official channels. Mercy was a one-industry North Carolina town of less than five thousand in danger of shrinking into oblivion. The textile mill was taking a beating from imports.

The Study Club was a book club, a support group, and a force to be reckoned with. While their husbands struck deals over lunch in clubs still dominated by white males, their wives held on fiercely to their own pockets of power. When the need arose, these hothouse blooms could shake loose an amazing amount of cash and clout. They got what they wanted without breaking a sweat, raising a voice, chipping a fingernail, or bothering with official channels. Mercy was a one-industry North Carolina town of less than five thousand in danger of shrinking into oblivion. The textile mill was taking a beating from imports.

The Study Club’s projects were invaluable to the community—the removal of asbestos in the high school; the fire department’s new hoses and uniforms; monthly contributions of canned goods to the local food bank. Any member could bring a need to the group. A majority vote determined action.

On this unusually warm day, with the sun cooking the Jaguars, Mercedes, and SUVs parked outside her house, Irene was coolly determined. She was club president, program chair, and commander in chief. With a jerk on her silk jacket hem and an unconscious straightening of her spine (an action hot-wired into her body by a mother obsessed with posture), Irene brought the group to order. “I’ve been volunteering two mornings each week at the high school library. And it has been quite an eye opener. Librarian Nancy Sandhart has her hands full. The attitudes of today’s youth are appalling, and as we all know, Nancy is not exactly a dominant personality. In short, I found the library itself lacking in control and its contents nothing short of questionable.”

Irene upended a Nieman Marcus shopping bag and poured books onto the ornate tile floor her contractor husband Arthur had special ordered from Italy. The befuddled members of the Study Club stared at the mound of literature. They were familiar with many of the books; some like Faulkner and Twain had been around when they were in high school. Other books such as the Harry Potter series looked new and were favorites of their children and grandchildren.

Irene nudged the pile with the toe of her black Prada. “Our children have complete and unrestricted access to this filth. Nancy makes no attempt to guide the young and impressionable toward more appropriate reading. She says she’s too busy.”

“Nancy buys these things?” asked seventy-six-year-old Arabella Richey, wrinkling her nose with distaste at a book about the adventures of a character called Captain Underpants. Arabella, wife of the bank president, was a mystery junkie and not ashamed to admit it.

“Apparently, they come out of the library’s budget. Many were requested.”

“People asked for this?” Arabella poked the underpants book with her cane.

“The children did.” Irene swept her hand across the pile. “In effect, ladies, we paid for them. This is our tax dollars at work.”

Several members looked at the heap in consternation.

“How can you be sure they’re all filth?” asked a soft voice. Irene turned to Julie Masterson Clark, a thirty-five-year-old who sneaked romances into her shopping cart at the grocery store. Their daughters were on the same soccer team. Julie’s grandmother founded the Mercy Study Club in 1919 as a place “where women of intelligence and culture could shine, keep abreast of the events of the day, and exercise their minds.” Julie’s mother had been a past president and a respected member until her death five years ago.

“Have you read any of them?” Julie asked.

“I’ve perused all of them,” Irene snapped. “I also consulted some librarians I know in other towns. And I found tons of information on the Internet. I even read some of those blogs. Most of those people are idiots, but a few were insightful.”

“Obviously, you’ve done your research, Irene, as usual,” said Arabella, popping a petit four into her mouth, whole. The woman was scrawny, not a muscle left in her pampered body, but she could pack away French pastry like a sumo wrestler.

Irene balanced a pair of half-moon reading glasses on her nose and opened a dainty and expensive leather journal. In it was a nutshell description of every book in the pile. As she read the description of a book, she roamed the room, pulling books from the pile and tossing them at the feet of the members. Members scooted away as waves of “filth” edged closer and closer to their well-shod toes.

“The Stupids Step Out,” Irene said. “Describes families in a derogatory manner and might encourage children to disobey their parents.”

Arabella huffed in disgust. “That’s an absurd name for a family, fictional or otherwise. What if Tolstoy had called her Anna Idiot instead of Anna Karenina?”

Arabella got no argument from Irene, who constantly fought the battle for eloquent language with her own children. She thought “suck” should be something you did with a straw, not a description of your homework. She continued, “Forever by Judy Blume. Contains profanity, sexual situations, and themes that allegedly encourage disrespectful behavior . . . Personally, I don’t want my daughter reading any of Blume’s books.

“Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury. One California library gave students copies of the book with all the ‘hells’ and ‘damns’, pardon my French, blacked out.”

“Not a bad idea, if you ask me,” said one member.

“I agree,” Irene said then went on to the next book. “A Light in the Attic by Shel Silverstein. Encourages children to break dishes so they won’t have to dry them . . .”

Irene paused for dramatic effect, watching the other members of the Study Club shift uncomfortably in their seats. She was a forty-five-year-old woman married for twenty years to a man who liked to get his way. She was also the mother of a sixteen-year-old son who thought he was smarter than she and a seven-year-old daughter, who, like her father, tended to bulldoze her way to her desires. In a family of power brokers, Irene had learned the value of controlled silence.

Julie cleared her throat and attempted a half-hearted smile. “Irene, surely when you were a child, you too hated doing the dishes.”

Irene peered over her glasses at Julie. “We had a maid for that. Even so, there is never an excuse to take a hammer to the Wedgewood.”

Julie looked to the others for help. Several members refused to meet her gaze. “But, Irene, some of these are classics—Faulkner, Steinbeck, Twain.”

Irene shoved William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying under Julie’s nose. “Masturbation and abortion.”

She pushed John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath toward Julie. “Takes the name of the Lord in vain. Repeatedly.”

At Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Irene sighed. “Where do I start? It’s a challenge magnet. I think they ought to replace the N-word with the word slaves, just like that professor suggested.”

Mary Sue Hampton, a mother of five who refused to allow even her three-year-old to interrupt her afternoon reading time, sliced the tension in the room. “What is it you think we should do, Irene?” Forty-year-old Mary Sue was known to take a scalpel straight to the heart of a situation. She had time management down to a science. She made schedules of piano recitals, ballet lessons, and soccer games on her personal laptop computer, printed out copies, and posted them weekly in the kitchen, bathroom, and children’s rooms. She was a born CEO and could easily have taken over her father’s successful textile business.

Irene sat, tugged at the hem of her already neat jacket, and crossed her long, slim legs. Patting her hair, which was never mussed, she announced: “I think we have to ban.” A soft gasp went up from the group. “Remove them from circulation—permanently. At the very least, they should be weeded from general circulation and stored safely on reserved shelves. Where they can be controlled.”

__________________________________________

Want to read more? Get your copy of Book of Mercy today. If you can’t find my books in your local bookstore, ask for them. Ask your local library to carry my books in their collections. Thank you for being a reader and supporting not only my work but those of many authors.